4 Traits Of Highly Effective Basketball Drills

"Make the practices like games and the games like practices" - Don Meyer

Basketball coaches are always searching for new drills and the internet is happy to provide. A simple Google search yields over 8 million web pages offering basketball drills. YouTube has over 172,000 videos containing basketball drills. With so many drills at our fingertips online, what criteria should we use to identify the most effective ones?

At Breakthrough Basketball, we have been studying the effectiveness of various coaching strategies in basketball, as well as in other dynamic, free-flowing sports such as rugby, soccer, lacrosse, and hockey. We paid particular attention to two key words when it comes to learning new skills: Retention and Transfer.

Retention refers to the ability of an athlete to repeat a movement over time. If Johnny learns a step-through on Monday and can successfully repeat the same move in Tuesday's practice, he has retained the skill from one day to the next.

Transfer refers to Johnny's ability to take what he has learned in practice and apply it effectively in a game. If Johnny can use his new step-through move to beat an opponent in Friday's game, his skill has transferred from practice to competition.

The goal of our study has been to identify the most effective ways to construct practice drills to maximize a players' ability to retain their learning over time, and transfer it effectively to a game.

Four Questions To Ask When Evaluating The Effectiveness Of A Drill

Question 1: Does the drill have a SPECIFIC PURPOSE?

According to Lisa Bluder, Head Women's Basketball Coach at the University of Iowa, coaches should ensure that every drill used has a clear purpose. Coaches should know exactly WHY they use each drill in their practice plan.

Consider this, perhaps you want your guards to finish with more consistency on the fast break.

Typically, players struggle to finish in transition because they are attacking at a high rate of speed, and defenders are rotating back to protect the rim. However, there may be specific circumstances that a player struggles with. The more specific you can be in identifying the exact situation you want to improve, the better you will be able to match an appropriate drill to teach the desired skill. Do you want players to improve attacking in one-on-one situations? Do you want them to be more effective with a numbers advantage, or at the back end of your press break? When considering the purpose of a drill, be as specific as possible.

Understanding the purpose of the drill naturally leads to question #2.

Question 2: How effectively does the drill address your purpose?

Does the drill simulate the EXACT SAME situation as it occurs in a game?

In order to score more frequently in transition IN GAMES, you must mimic game situations by including DEFENSE in your transition drills. Running a 3-man weave or any other full court passing or finishing drill without defense will not meet your stated purpose, and therefore should not be used to improve your fast break offense.

If your team struggles to convert when they have a numbers advantage, search for drills that mimic your team's transition opportunities as closely as possible. In our system, we have a lot of opportunities to go 2 on 1 or 3 on 2 in transition, but rarely do those situations occur with the defenders already standing at the goal (as is the case in most 3 on 2 drills).

Our challenge is learning to recognize a developing situation while everyone is running toward the basket. Defenders usually get back in the middle of the floor - sometimes they are ahead of the ball, sometimes they are not. To be the most effective at building skills that transfer to a game situation, we need to design advantage drills where defenders are running somewhat randomly through the middle of the floor while we attempt to get organized into our appropriate lanes.

Continuous 3 on 2 is a popular drill because it's fast paced and appears to simulate a common game-like scenario. However, we never experience a 3 on 2 break for more than 3 seconds in a live game. Trail defenders are always chasing the play which accelerates the need for quick decision-making. If players do not experience the pressure of trailing defenders, they are less likely to transfer their practice skill to the game because they are training for a situation that does not occur EXACTLY THE SAME WAY in competition.

Question 3: Is the drill efficient?

ACTIVITY and PRODUCTIVITY are not the same thing.

Another important aspect of drill evaluation is how many repetitions the players are actually getting in a drill. Often a busy gym can be mistaken for a productive gym. In order to find out exactly how efficient your drills are, I advise coaches to use managers, injured players, assistant coaches, or even parents to COUNT the number of shots, passes, dribbles, etc. a player performs in the drill. You might be surprised by the results.

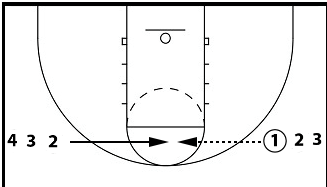

Let's look at a common shooting drill as an example. Below is a warm-up drill that is used in many practices. I recently watched a team perform this drill where the team was divided into two groups of approximately 10 players (the drill was done at both main baskets in the gym).

To test the drill's efficiency I chose one player to watch, and counted the number of seconds between her shot attempts. Here's what I observed:

- Sally took only 10% of the total shots in the drill (1 of 10 players at her basket)

- Each drill repetition (1 shot) took about 2-3 seconds

- Sally shot the ball on average once every 20 seconds (3 shots / minute)

- In the 4-minute drill, Sally attempted 14 shots and made 13 passes

Regardless of how busy the players may have looked passing, shooting, and switching lines, the drill is horribly inefficient if the purpose was to get as many shots up as possible.

How do you make basketball drills more efficient?

Consider the common practice of partner shooting. Player A shoots the ball - grabs the rebound - and passes to Player B. Player B repeats the same process. Let's use the same measurements we did with Sally above to evaluate this drill's efficiency.

- Player A shoots 50% of the total shots

- Each repetition (1 shot) takes about 3-4 seconds

- Player A shoots the ball every 7 seconds (8 shots / minute)

- In 4 minutes each player attempted 35 shots and made 35 passes

This is much more efficient than the 2-line passing drill above. However, even this drill could be more efficient. Here are some suggestions for getting more shooting repetitions:

- Player B rebounds while Player A shoots. Switch the players after 2:00. This variation may not condition your players in the same manner since they are not chasing their own rebound but it will increase their repetitions. Players will typically get 15-20% more shots with a designated rebounder than they do rebounding their own shots.

- Use more basketballs. Instead of two players partner-shooting, have three players use two basketballs to increase their repetitions. Each player shoots and gets the rebound. As soon as Player A shoots, Player B shoots and repeats the process. Player A passes to B, B passes to C, C passes to A. We utilize this drill daily on all six of our baskets. Our players get an average of 40 shots per player in 3:00.

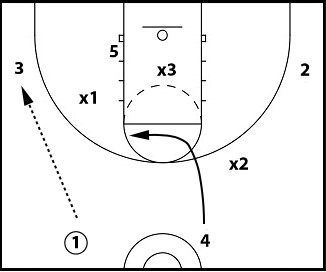

The same analysis can be applied to team concepts. For example, scrimmaging 5 on 5 is incredibly inefficient if the goal is to increase repetitions of a specific component of your offense or defense. If you want to improve your pick & roll offense, the best way to do this is to practice live pick & roll situations as much as possible. Here's how:

- Play 2v2 on every available basket.

- Allow players to attack from the same spots on the floor where they would receive the ball screen in the offense.

- Give the offense ONE attack - then rotate quickly by...

- Playing Make It, Take It - If you score - you stay on offense (up to 3 in a row). The next group always enters on defense.

- Have the defense switch to offense, with the new group entering on defense.

- This will yield repetitions every 5-6 seconds (10-12 pick & rolls / minute)

- In 4:00 that's almost 50 pick & roll sequences at every basket!

Without compromising efficiency, you can make this more game-like by adding a help-side defender in the opposite corner and allowing 3 to shoot / backdoor / offensive rebound. The drill rotates the same way.

Again, repetitions should occur every 5-6 seconds which yields 50 pick & rolls in 4 minutes.

The most important factor in analyzing your drill efficiency is to COUNT the repetitions of the specific action you want to improve. It's impossible to improve efficiency without counting!

Question 4: Does the level of difficulty match the player's ability level?

Drill constraints should produce a 50-60% success rate.

In order to maximize a player's improvement, players need to spend as much time as possible at the edge of their ability level. When developing new skills they should experience both success and failure as they learn. Too often coaches do not adjust their drills to meet the needs of the players performing the action. Drills that are too easy do not engage the player's attention when the struggle to find success is no longer present.

If a player can successfully perform a movement or skill correctly in 60% (or more) of the repetitions, then it's time to make the drill more difficult!

Likewise, if a player cannot experience success at least half the time, then the drill needs to be simplified to match the skill level of the athlete.

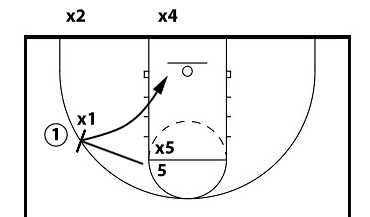

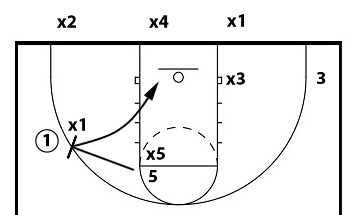

It is important to understand how to make accommodations within a drill for players with varying ability levels. For example, we like to run a continuous transition drill that varies the number of defenders back on defense. Our starting five is challenged to score 5v4 using our transition options, so we will typically send four players back on defense, or will send three back with one or two more trailing the play. This level of defense is appropriate for our top group.

However, our second team may struggle to score 5v4. They may not see the options well, or have trouble establishing appropriate spacing in transition. Consequently, we will vary the number of defenders back on defense so that they experience both challenge and success. In 10 possessions, we might assign defenders to gradually increase the difficulty level as we observe their performance in the drill. A progression for our second team might look like this:

- 2 Possessions 5v2

- 5 Possessions 5v3

- 2 Possessions 5v3+1 (trail defender)

We also encourage our defensive players to behave randomly. At times, as in the drawing above, we encourage defenders to play very aggressively and look to pressure the perimeter players. At other times, we have the defense rush back in the lane to take away any penetration by the offense. The drill becomes more difficult for the offense when the defense behaves in unpredictable ways. The offense must read the defense and make an appropriate decision on the fly just as they would in a real game.

When players are placed in challenging situations that allow them to experience both success and failure they are more likely to be engaged. That engagement typically yields more effort, better problem-solving, greater retention of skills from day-to-day, and greater transfer from practice to a game.

Don Meyer said it best:

"Make the practices like games and the games like practices"

Every great basketball drill has a specific purpose that simulates game-like situations. Great drills make the best use of time by maximizing the amount of repetitions each player receives. Great drills are challenging and offer the opportunity for both success and failure in almost equal proportion.

How many great drills are you using in practice?

Food for thought.

Footnote

The art of coaching requires an incredible level of perception to identify exactly what your team needs to improve. Understanding the specific cause of a team's deficiencies helps to identify the purpose for your drill work. However, that requires more than simply identifying your weaknesses. To be most effective, you must understand WHY your team struggles with a particular skill.

For example, a low shooting percentage could be the result of any number of different causes that require different remedies.

- Poor shooting mechanics requires more physical repetitions. If your team can't shoot when undefended, they need maximum repetitions without defense to improve their form and confidence.

- Poor shot selection requires better decision-making in GAME LIKE repetitions. If players settle for jump shots when you would prefer post entries, create basketball drills that place players in a situation where they must decide to shoot or pass the ball into the post. If that decision is predicated on how what the defense is doing, then defense must be included in the drill.

- Poor offensive execution may require players to improve a particular aspect of the offense. For example, if spacing is an issue that destroys your offense then your drills should require players to move in coordination with one another. Situational, small-sided games are excellent teachers of spacing and decision-making. Identify when spacing becomes skewed, and create drills that simulate that exact action in practice.

Understanding the cause of your team's weaknesses is key to choosing the most effective drill to improve their performance. Not every drill will maximize efficiency, or be perfectly game-like. Every season, every team, and every player will require different interventions to maximize their improvement. The master coach identifies those needs and creates drills to help players improve where they are at right now. This is applicable at all levels of coaching.

Related Resources

- Game-Based Drills For Shooting, Ball Handling, Passing, Transition, and Scoring

- Game-Based Drills Education Series - Part 1: Create Your Basketball "Flight Simulator" and 1v1 Fill Up Drill

- Game-Based Drills Education Series - Part 2: Evolution to Better Drills, Sniper School, and 2v2 Pick and Roll Drill

- Game-Based Drills Education Series - Part 3: Benefits to Game-Based Approach, Hitting Curveballs, Perception Action Coupling, and 2v2 Drive and Kick Drill

What do you think? Let us know by leaving your comments, suggestions, and questions...

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Facebook (145k Followers)

Facebook (145k Followers) YouTube (152k Subscribers)

YouTube (152k Subscribers) Twitter (33k Followers)

Twitter (33k Followers) Q&A Forum

Q&A Forum Podcasts

Podcasts